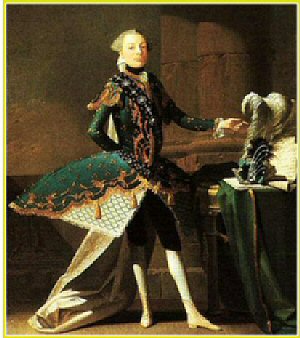

The castrato Carlo Scalzi, by Joseph Flipart, c. 1737

Note the peacock attire.

At the opera, audiences screamed “Love the knife, the blessed knife!” just as 1960s prepubescent girls once fainted and shrieked over John, Paul, George and Ringo. Here we have an example of “body modification” raised to an art form. Like today’s pop stars, the castrati were famous for their fabulous attire, lavish lifestyles and epic tantrums. Audiences mobbed them; women wrote them love letters. They commanded huge salaries and associated freely with the aristocracy. Farinelli, the most famous castrato of all, was for many years an intimate of the Spanish royal family.

Two hundred years earlier, the Pope had banned women from singing in churches and on stages. This, in turn, led to the castration of choir boys, so that the soprano parts would continue to be filled. By the early 18th Century, Italian opera became widely popular in Europe and in England. Handel-among many others who are now less famous-wrote for them, as the castrato voice had become the next great fashion fad. The finest castratos possessed a three octave range. Many received a top drawer musical education.

It is estimated that for a hundred and fifty years, at least 4,000 boys annually endured the operation—performed by barber surgeons and often at the behest of poor families, hoping to profit from the next great musical superstar. The physical facts of castration are simple enough to have been practiced from the dawn of human society. The ducts leading to the testicles were snipped causing the external organs to wither. Prime candidates were boys from the age of 8-12, although one famous castrato, Senesino, who was Handel’s Primo Uomo (leading man) was “made” at the age of 13, perhaps by his own barber father, a man with strong aspirations to a finer life-style. Some boys died from an overdose of opium or from strangulation when pressure on the carotid artery was used as “anesthesia.”

Lack of testosterone causes the external genitalia to remain boyish; prepubescent breasts appear. Bone joints don’t harden normally, so long arms and long ribs result. Those long ribs in a full-grown body leave plenty of room for lung capacity, and the end result was a sound that one historian calls “Pavarotti on helium,” a knock out combination of pitch and power. Lungs trained every day with vocal exercises pushed man-sized breath through child-sized vocal chords. The effect has been called “ethereal” and “other-worldly.”

A 1902 recording of Alessandro Moreschi,

the last castrato, aged 44, past his prime.

It was fashionable among fast-living aristocratic women to boast of sexual encounters with their musical idols. Certainly, castratos would provide the ultimate “safe sex” in the days before contraception, but much of this was probably wish-fulfillment. The age at which the operation was performed determined whether erection remained a possibility. However, lack of sensation could impart endurance to a man who had retained this capability. As one anonymous lady poet wrote of the famous Farinelli, most men were only “bragging boasters,” while “F****lli stands it to the last.”

Charles Burney, an 18th Century musical historian, traveled widely in Europe. He reported plump castratos he encountered in Rome who wore brassieres and pimped themselves out as either women or men. He never was able to meet a barber-surgeon who would admit to performing the operation, for, like many fashionable things, it remained illegal. In every Italian town where he inquired, he was pointed to its nearest neighbor.

The character of Signor Manzoli, Maria Klara’s voice teacher, was based on what I’d learned about the castrati, about their artistry and about their physical appearance. As Manzoli is an old man, long past his prime when Klara comes to him for lessons, he has grown heavy. His heady time of fame and fortune is long over. Like so many other musicians of the period, the decline of his fame has brought him face to face with a difficult and obscure old age. I chose the name because of a familiarity with the generous Giovanni Manzuoli, a castrato who was a good friend to the young Mozart and who is often spoken of in the Mozart Family Letters.

Interesting further reading or listening on the subject: Farinelli, the celebrated Italian castrato singer of the 18th century.

From the modern art movie “Farinelli,” where the voice of a coloratura soprano and a countertenor were combined for the musical selections. Fabulous 18th Century costumes, music, and exotic content!