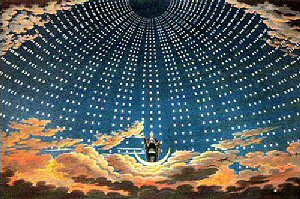

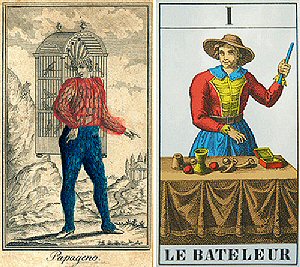

It has been said that The Magic Flute is a pipe dream in which “the ultimate secret is revealed, only to be forgotten again upon waking.” It certainly is filled with occult and masonic references, which would suit both the popular taste of the times (1791) for “magic,” and also the taste of Mozart and his friend Emmanuel Schikanader, impresario of the Theater am Weiden, who were fellow masons. Magical numbers of three (3 ladies, 3 genii) and nine (Sarastro’s priests) appear repeatedly—and, of course, musically, too--throughout the opera.There are a host of pairs and opposites among the highly symbolic characters: male/female, day/night, noble/common, perfect union/perfect disunion. There are trials by fire and water. Some writers believe that because “Masonic secrets” are revealed in the course of the action, the Brotherhood may even have been responsible for the composer’s sudden demise. While I don’t subscribe to this belief, there certainly are many occult references scattered throughout the muddled libretto.

It is muddled, too, even for a fairy tale. Mozart had already begun to set music to a script, when they realized that Schikanader’s arch rival, the Leopoldstadt Theater, had already launched a singspiel called The Magic Zither. Suddenly, the writers and the composer had to change gears. This they did by the simple expedient of switching the Queen of the Night from a good character to a bad one and similarly changing her husband, Sarastro, from an evil tyrant to a benevolent “Philosopher King.” It shows clearly in the first act, when the emissaries of the Queen, the three ladies, give the wandering Prince good advice as he begins a quest to find a true love.

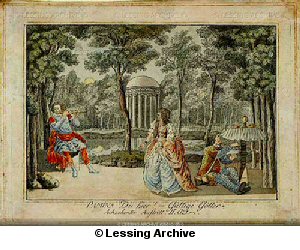

In the end, however, no one much cared, then or now. The music and the spectacle were and are still sufficient to create a luminous piece of theater. Goethe’s mother wrote: “No man will admit he has not seen it. All craftsmen, gardeners…and even the “Sachsenhausers” (a rural suburb of Frankfort), whose children play the parts of apes and lions, are going to see it. There has never been such a spectacle before.” (This is praise, even if the German word for spectacle carries a double meaning: “show” and “uproar.”)

As Frederich Blume in his essay on “Mozart’s Style and Influence” remarks: “To compose music for all; music which would suit both the prince and his valet…to compose music that had to be both highly refined and highly popular was a new and unprecedented task.” Two-hundred and twenty-one years since this opera premiered, and it’s still going strong. The Magic Flute remains the perfect “first opera,” the one parents most often use to introduce their children to, not only Mozart, but to this peculiarly western form of High Art.