May 16, 1852

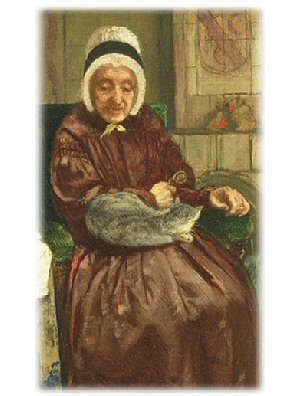

Bird claw fingers intertwined, upright, regarding flowering June, sits Fraulein Anna Gottlieb. She lives alone in a room on the first floor of an apartment in the Alsergrund suburb of Vienna. The one room is, however, choice, for it opens onto a brick patio alongside the landlady’s garden.

So long ago, yet those ancient battles still deal pain. Fraulein Gottlieb recalls running to hide, squeezing herself inside a linen cupboard. There she cowered for anguished eternities, knobby knees against her chin, inadequate fingers stuffed into her ears.

Long ago, before the time of Napoleon and for years after his demise, Anna was a famous Singerin-- singer. Although she has lived a very long time, she has been careful with her money. She can pay rent, have her simple meals prepared and her lodgings cleaned by the landlady’s servants.

Anna Gottlieb’s eyes are the only beauty remaining in the ruin of what was. They shine with the silence of eighty years lived with complete attention.

So straight her cricket body -- a habit acquired in earlier youth.

Fraulein Gottlieb never shrinks from admitting that her stage career was begun in the ballet-- although then as now, this is an entirely disreputable profession.

Old lids close in the welcoming warmth of an early June sun, but she does not sleep. Instead, Fraulein Gottlieb drifts; she remembers.

By the age of nineteen, her mother’s glory days were done. For a few shining years, she had been the star of an elite corps de Ballet-- the Imperial Figuranti. Afterward, beginning with Anna’s father, Mother found a succession of men to keep her.

Anna had managed quite well without belonging -- officially or otherwise -- to any one. Her success had continued for more than thirty years.

“Before you were born,” Mother had often said, “I could fly and float like an angel. Afterward, it was as if I carried an anchor.”

It was not a kind thing for a mother to say to her child. Anna understood now that it had been not only herself, but her sober musikerfather who had comprised the anchor.

“Poor child.” Mother, makeup smudged, her late arrival home unexplained, sat unrepentantly before an open bottle. She reached, breathing wine, to tug Anna’s dark curls, so unlike her own gleaming chestnut. “Of all the rich Papa’s you might have had! Instead, the capricious womb opens for the seed of a poor musiker, a fellow I lay with out of charity.”

If Anna’s hard-working father overheard--which Mother, in her cups, often contrived he would--he’d retort, “Yes, I was the only one willing to marry you. Fool that I was to imagine the devotion of an honest man could reform a public woman.”

Then Mother would scream about Papa’s failure to rise from the ranks of the orchestra, about his lack of money. In turn, he would accuse her of infidelities past and present.

Ordinarily Anna’s father was a gentle man, but Mother, like Circe in the story, could wave a wand of words and turn him into a beast. The bruises she displayed to her woman friends sanctioned each of her repeated transgressions.

Bees buzz among tall spikes of lavender. A diminutive calico cat, tail curved with healthy confidence over her back, prowls a thicket of herbs: sage, blooming dill and hyssop. The cat is Fraulein Gottlieb’s, a constant companion. The cat’s tail sways like a loon’s neck; her body is immersed in a green river of salad.

It’s sad, Anna thinks, but I don’t actually remember Papa. There is the miniature, of course, but the painter was not very good. That skewed daub is less than an echo.

What I do remember is a warm lap, an agreeable leathery smell, hugs, and scratchy Papa kisses. The clearest memory makes a return when I look in the mirror and see my own eyes -- or the blurred fingers of a violinist deep in his art.

Over her head, the sparrows who made their nests in the ivy have begun a noisy squabble. Their chatter has made a background to every waking hour as long as she can remember, even back to the time when she’d slept in a child’s truckle bed tucked into a corner of her parents’ room. She remembers the sound of shift and snore, the creak of bed ropes as they turned.

Above, in the second floor apartment, a careless cook sets a pan on fire. The rank smoke of burning butter, accompanied by cries of exasperation, pour from the window. In Anna’s memory, another fire surges, crackles. The present odor changes, now redolent of tallow.

Where she spent her childhood, deep in the labyrinth of the old city, houses leaned their lofty heads together, as if gossiping across the street below. The sun had to get quite high before it could so much as insert a finger into the poorest apartments.

Here in the Alsergrund it is newer, not so crowded. There is light, light for everyone, be they rich or poor.

The cat leans against her knee. She first strokes, and then pats her withered thigh, saying, “Kommst du, meine Mutzie.”After the moment of hesitation, the cat jumps up. Then, turning around, cool paws knead the linen of Frauein Gottlieb’s dress. Finally, she settles to gaze at her aged mistress, green eyes full of contentment.

Fraulein Gottlieb thinks: It’s all the same. I sat even as I sit with my cat in my lap, waiting for a servant to bring porridge. Back to the beginning, even to needing the help of others, even to my noisy stomach growling.

There have been many Mutzies over the years: black and white, mittened, calicoes, the affectionate ginger tigers. What polite, useful creatures cats are, far more agreeable and sensitive than most people! This Mutzie fairly smiles; she carries that tiger tail of hers straight as a poker whenever she presents Anna with a mouse.

It is a luxury not to be awakened in the wee hours -- when one has just drifted off, at last -- by gangs of mice romping across the coverlet. Any rodent so unwary will not live to tell the tale -- not around the claws of this dear and oh-so-quick Mutzie.

Mother continued to perform after Anna’s birth. She paraded her beauty in masques; she danced in the courtly divertissement that proceeded the opera, and even “lowered herself” to play for laughs in the physical, knock-about mime of puppet dances.

Even in what she professed to disdain, Mother excelled. Those puppet dances became a particular specialty. Everyone agreed that she did the wittiest “peasant with a basket” ever.

Mother instructed Anna. She was no gentle teacher, quick to cry “Clumsy!” and slap. Nevertheless, by her eighth year, Anna often went with her mother to perform. Cherubs and fairies, pagan children sacrificed by their parents -- these were her roles.

Costumed in scanty muslin, dark curls loose, Anna had yawned and shivered through many late nights in the marble chill of Vienna’s great houses. Mother did see that she had a wrap for her childish body after performances, and taught her to beware of this one and that, vicious old men like old Count von S, who snared the hapless children of servants with as little compunction as a spider takes flies.

Although Mother rarely praised, Herr Franck, Master of the Court Figuranti, asked for Anna almost as much as he asked for her best friend, blonde Katherel. In this way, Anna came to understand that her performances gave satisfaction.

Papa praised, but he didn’t want his daughter to remain in the ballet. They needed what Anna earned, but her father hoped she would lead a respectable life, so he taught her music. All his hopes rested in his daughter’s sweet, supple voice.

Fraulein Gottlieb recalled singing for Papa’s orchestra friends. Such encouragement they’d given, always applauding, “Gottlieb’s Kleine Nachtigall--Little Nightingale!”

When they’d said that, she had swelled with pride. Anna couldn’t think of a time when she hadn’t known the difference between “nightingale” and mere “canary”.

Papa had had her sing scales every day. He also found time to teach her to read, to write, and to figure. He sent her, along with other musiker children, to a teacher of French and Italian, the languages of the stage. He dreamed that his Anna would become a great Diva.

Her parents often quarreled about this. Mother, who could barely read, (although like most performers, she had, by ear, Italian and some French) thought education was wasted on a daughter.

“Girls don’t need much to get by. As for her voice, she’s a soubrette, nothing grander. When she’s ten, Herr Franck says he’ll take her into the Figuranti. Even plain as she is, those legs of hers will get her a man quicker than you can blink.”

Mother, Fraulein Gottlieb knew had been unable to imagine a larger life for her daughter than the one she’d had herself. There was no longer any resentment; the past was simply a fact.

Clothes and manners, Anna thought, have changed, and not for the better. Factories, noxious coal fires and hypocrisy are the hallmarks of this new age. The sighing basset horn is forgotten, as is the plaintive sob of the obe d’amore. The dainty, precise klavier has--like a spoiled child--grown into a gross, blooming pianoforte.

A few things were the same. Oxen dragged wagons into town, their great heads nodding in yoke like agreeable philosophers. Sleepy servants, teeth chattering, still ran errands at midnight.

Butter and sugar on my porridge, three meals today just like yesterday’s, a warm slurry easy on the stomach. There are chickens in the street, sparrows quarreling in the ivy--and men and women breaking each other’s hearts.

Fraulein Gottlieb gazes into the rectangle of June blue that illuminates the little garden. She remembers a party, held on a day when the sun in splendor blazed in a cerulean sky. Mother had hated performing at garden parties--there were grass stains and insects as well as the usual drunken noblemen with which contend--but to musiker brats, summer was the best party time. There were always other children with whom to play, performer’s children, like herself, to whom these affairs were a kind of education. They had run free in lavish gardens, big as city blocks, devising their own ballets and plays, had rejoiced to be out of the eternally shadowed streets of the medieval town.

In winter, there were great halls to race through, tapestries behind which to play hide and seek. As long as they didn’t get in the way or make inappropriate noise, no one cared what they did.

The first thing was to find friends, then to steal a glass or two of wine from the tray of a passing servant and share it out. Next, enjoying the giddy sensation that reliably followed, they’d wander.

Prince Cobenzl owned one of the finest gardens. There were roses: reds, whites, yellows and pinks. So many shades, so many scents, not only bushes, but an entire corridor lined with regiments of rose trees, like dowels topped with powder puffs of green and blush. Katherel joined Anna in sampling the fragrances. An older boy--Theo--watched with disdainful male incomprehension, especially after she and Kath sniffed themselves into a fit of violent and prolonged sneezing.

There was also topiary. Beneath that deceptively cool, penetrating June sun, they roamed for an hour, gawking at an endless parade of dragons, peacocks, horses and rabbits, all cut from thick green boxwood.

As the orchestra tuned, they became part of an anticipating throng in the outdoor amphitheater. For ease of passage, they slipped hands and made their way separately among the elaborately coiffed ladies, like great ships of silk and brocade, sailed athwart their way.

The top step of a newly erected pavilion was a good place to get a view. In a passion for all things classical, Prince Cobenzl had erected a miniature replica of a Roman temple. There, at the top of nine marble steps, they’d looked across the white and silver of the audience to the red coated orchestra. Anna spotted her Papa among the violins.

Behind the slim crescent of musikers, stood an enormous oak. Mighty limbs raised, it was a leafy, bark-armored Atlas of such potency, she imagined that, all alone, it very well might support the sky.

Into breeze and bird song, the orchestra began, a spirited composition which Anna never had--in all her musical days--heard. The opening allegro was so beautiful that it curved her lips into an involuntary smile.

An erect little fellow was Concertmeister--first violin. Anna did not recognize him. Though barely more than a boy, he led the orchestra, finally sweeping the joyful melody into a passionate solo. Like the other performers, he wore a white wig, a red jacket and black breeches, but the cascade of glorious sound from his instrument was as brilliant as this once-a-summer perfect day.

The audience closed their eyes and threw back their silver heads as if in ecstasy. Some swayed. Champaign and wonderful music fountained high and then fell back over the assembly in a sparkling waterfall.

Anna was lifted, up through the overhanging canopy of green, straight into the bowl of heaven. The fleecy cloud sheep which had dotted the morning sky had now wandered away. The aching blue suffered no interruption, except for the occasional flash of hunting swallows.

Anna had seen ballets about Orpheus, for whose music the creatures--and even the rocks and trees--had danced. Suddenly, her girlish imagination ablaze with music, she’d seen the rough bark of the oak pulse, as if a heart beat within. The venerable oak appeared to be breathing, exactly like her own warm, thin self.

Disconcerted, she tried to shift focus to the remarkable violinist. That was when she heard it.

“Orpheo,” a deep voice intoned.

Properly, at least to her way of thinking, the mysterious speaker had used Italian. Dizzily, she looked around for someone to acknowledge the words, but met only the questioning gray eyes of Kath.

Then, while the wonder of this still hummed, a long-nailed hand roughly seized Theo’s shoulder.

“There you are!” the woman grumbled. It was Madame De Vry, the dresser.

“Hurry!” she hissed. “The ballet comes next, and you children must be ready.”

She spread her dark skirts and shook them. They fled, chicks before the flapping wings of an impatient hen.

Anna went most unwillingly. To be parted so suddenly from that music made her ache. It was as if she had been woven into a glorious, seamless fabric--the magical violinist, the venerable oak, herself--only to be torn away, a lone thread cruelly plucked from a great whole.

As mother knelt, settling the garland upon Anna’s curls and attaching the harness which supported the wings around her flat chest, Anna asked, “Who is the new Kapellmeister who plays so wonderfully?”

“Kapellmeister?” Mother sniffed; she tugged to straighten the wings. “Kapellmeister?” She said it again as if Anna had no idea what that high honorific meant. “He is only the son of a provincial music master.”

“Yes,” Madame De Vry chimed in, “this is only Leopold Mozart’s boy, young Wolfgang.”

So long ago--it came back in pieces, in long waking dreams as she sat on the patio, gazing at the ruffling salad. Some days she remembered so clearly: the touch of Kath’s soft hands, the scuffling strike of a dancing foot upon parquet, a soprano crescendo drawing down holy tongues of fire, the haunting song of a nightingale, the wine-and-sugar of a lover’s secret kiss given in the dark Vienna Wood.

It was commonly said that Death was always flying towards the light. Fraulein Gottleib supposed that close as she was to her own rendezvous, she ought to pay more attention to such things, but she could not.

No, Heaven could not be the silly stuff servants believed and priests taught! Heaven, she thought with habitual decision, is a fabulous garden party, a summer blue sky traversed by winged spirits of air.

Paradise must resemble Prince Cobenzel’s gardens, full of roses shedding fragrance and creamy petals. In the forest beyond, she would once again see the ancient Vienna woods, where there were trees so old they’d seen the Romans came and plant vineyards on the sunny slopes of the Danube.

Heaven will be singing and dancing to the music of Mozart, my Beloved Orpheus. Voice and body whole, I shall enter the burning joy of creation.